In China, a video recently circulating online shows a man, accompanied by a group of people including a person in a police uniform, kicking in the door of a room and pulling out a teacher, with his hand firmly gripping the teacher’s neck. The rough behavior in the video (link in Chinese), which seemingly left the students terrified, has caused serious discomfort. Later, the local government made a statement (link in Chinese) explaining the incident, and promised to seriously deal with the problem of the man’s improper law enforcement.

In my opinion, no matter what, we should respect teachers and advocate learning as a way of changing one’s destiny. The public’s feelings regarding these traditional virtues should never be undermined. Like school teachers, those engaging in after-school tutoring also impart their knowledge to students. Despite recent regulatory changes to the industry, these teachers are not criminals and should not be disgraced.

In China, education is deemed as a foundation of the country. Admittedly, the “involution” in education — which often means excessive competition — could result in insufficient innovation and slow economic growth. Therefore, efforts to change this are being done by the authorities and are supported by a large number of parents.

There are many policy measures available to guide adjustment within the after-school tutoring sector, which many believe has intensified competition. For example, a practical move would be to send a clear signal to the capital market that the government aims to prevent the rapid expansion of the industry through overcapitalization, then announcing that these enterprises are prohibited from listing. In this way, it is possible to make policies more predictable, giving capitalists time to react. A market-oriented economy should use policy signals to guide market adjustment, and lower-level government’s improper or excessively strict enforcement of policy should be prohibited.

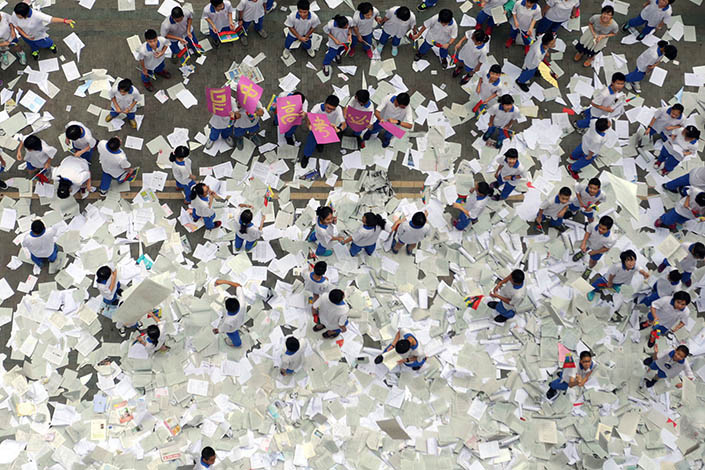

There are multiple reasons for excessive competition in education, which has boosted the development of the after-school tutoring industry. First, China has an enormous population and an intensely competitive talent market. This is also why Chinese students have to work hard and most parents are willing to invest a lot in education. Second, although the nine-year compulsory education ensures relatively equal access to educational opportunities, resource constraints make it hard to implement a system that takes into account student differences. Third, it should be noted that students at all levels may have a real need for tutoring. Therefore, problems in after-school tutoring cannot be solved with a one-size-fits-all approach.

If it is believed that the industry has intensified society’s hunt for high scores through endless repetitive exercises, causing high scores but low abilities, then the solution should tackle the problem at the root. The emphasis should be on multidimensional talent cultivation and selection rather than solely on test scores.

If teachers are paying more attention to lucrative after-class tutoring than their jobs at schools, relevant policies can be issued to ban them from engaging in paid tutoring, preventing a conflict of interests. This issue can be completely solved by strengthening the professional norms for school teachers.

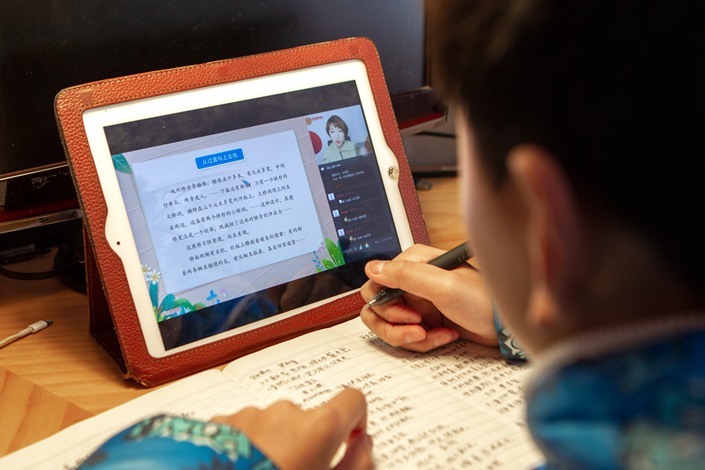

Currently, students still have real needs, although the recent policy has imposed restrictions. If the after-school tutoring industry falls into a regulatory grey area, it will become more difficult to control risks, and low-income families will face higher barriers to tutoring classes. Meanwhile, more than 1 million employees in the industry will also be impacted, dealing a blow to the job market.

We still need to rely on modern social governance to settle key issues, such as unequal access to educational opportunities, excessive competition, and low quality of education. In China today, the reality is that the education system does have flaws. For example, China generally lacks educational resources, children of migrant workers cannot attend school in the cities where their parents work, and poor rural areas lack teachers. What’s more, the gap between the existing quality of education and the talent needed to achieve China’s goals presents a major hurdle. This is especially the case in areas where originality is needed, such as technological innovation. This is something we need to think deeply about.

Given that public educational resources are in short supply and that it is hard to ensure sufficient resources in a short period of time, we should make good use of the market — a supplementary tool — and should be careful when restricting the supply side of the market so as to avoid counterproductive effects.

Author: Ling Huawei, Caixin Global

Ling Huawei is managing editor of Caixin Media and Caixin Weekly.